Women’s History Month: VHS highlights women’s integral role to advancement of medical care on Peninsula

In honor of Women’s History Month, Virginia Health Services is shining a light on the pivotal role women played in the advancement of medical treatment on the Peninsula.

VHS was founded in 1963 and for more than 60 years has strived to be the provider of choice for senior living, senior care, rehabilitation, home health and hospice. We recognize the value of our location in Hampton Roads and its rich history, which includes contributions to the medical field. And we’re proud to partner with Fort Monroe to celebrate women’s contributions to nursing and therapy this March.

We asked Fort Monroe archivist Ali Kolleda to share some of the former Army post’s history of women nurses and reconstruction aides, who were the precursors to occupational and physical therapists.

“World War I was a big turning point for the medical field, and specifically women’s involvement,” Ali said.

The research extensively shows the integral role of women’s work in the Army, well before they were allowed to enlist in 1943.

Virginia Health Services continues the tradition of supporting women’s roles in providing care on the Peninsula.

Civil and Spanish-American Wars

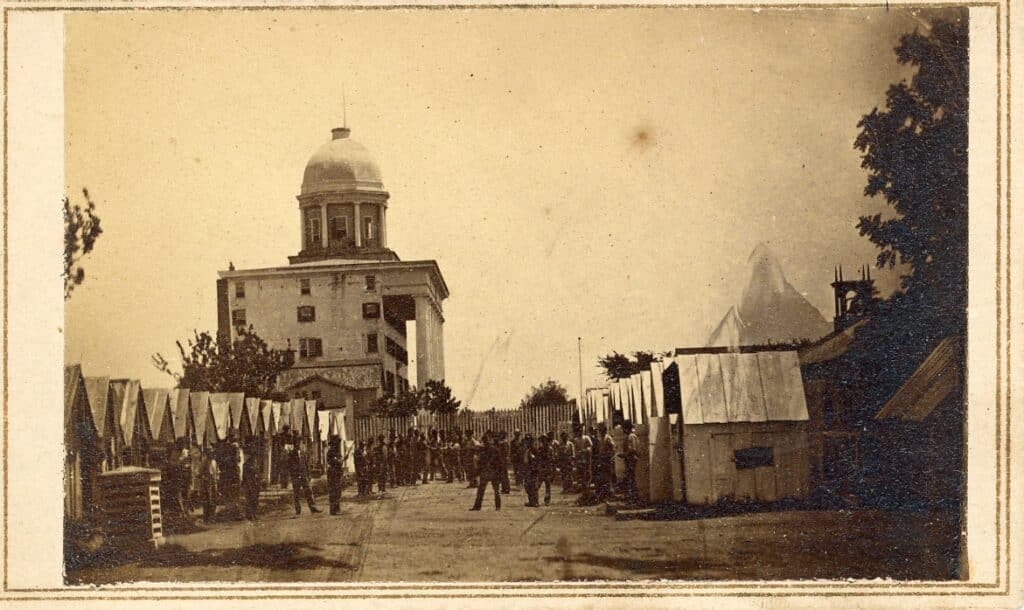

Fort Monroe was a hub for the treating of wounded soldiers during the Civil and Spanish-American Wars. It was considered easy to access along the waterways, and was the only Union stronghold in the South during the Civil War.

At the time, Ali said, “Fort Monroe was lauded as ‘a miraculous climate that could cure disease,’ and the Hygeia Hotel was meant to allow wealthy people to convalesce and ‘take to the waters.’ Hygeia was named after the goddess of health.”

Nurses were treating malaria en masse and wounded soldiers from combat.

During the Spanish-American War, articles are written about how exemplary the nurses’ care is when treating soldiers returning from Cuba, Ali said.

There were between three and four hospitals set up at Fort Monroe during the Civil War. The complex included the Post hospital, a requisitioned the ballroom at the Hygeia Hotel, the then-Chesapeake Female Seminary, a tent Hampton Hospital (for enlisted soldiers) and a contraband hospital at the Fort’s entrance.

They were huge complexes with hundreds, if not thousands, of nurses running them.

“They’re called volunteer nurses through Spanish-American War,” Ali said. They were taught at medical schools and apprenticeships through hospitals. Many nurses were trained through the Red Cross.

A circular published during Civil War (possibly by Dorthea Dix) advertised for “matronly women, widows – women who don’t have dependents,” Ali said.

Ali said that changes, especially during times of war. Some women would follow their drafted sons and husbands to the post as nurses.

“Lucina Emerson Whitney followed two sons who were serving in the 67th Regiment, Ohio Infantry, which was sent to Virginia,” Ali writes based on Fort Monroe archived documents. “She was assigned to the Hampton General Hospital (of the U.S. General Hospital, Fortress Monroe) in June 1863 where she served for the duration of the war.”

During this time, black women could not enroll in the Red Cross. There is not a record of black women as nurses at Fort Monroe during WWI.

Black women were contracted during the Civil War at Camp Hamilton (Phoebus) as nurses. Harriett Tubman was at the Fort during Civil War to inspect the contraband hospital. She was offered the job as head nurse – “we don’t know if she came back because the war was over at that point. We know she was here for three months conducting the inspection,” Ali said.

Records at the end of Civil War (1870s) show that black midwives delivered children at the Fort.

“They were here,” Ali said, “but wouldn’t have been officially considered Army nurses in the Nurse Corps.”

Army Corps of Nurses

Army nurses are at Fort Monroe consistently from 1901, not just times of war.

“(Training) becomes formalized in 1901 at the end of the Spanish-American War when the Army realizes they need a permanent body of nurses,” Ali said. “The Army Nurse Corps is created at that point. Army nurses are contracted, not enlisted, so there are no benefits. They’re not considered veterans. They’re simply civilian women contracted as nurses.”

They developed a community on the post. Ali said Fort Monroe has community activity bulletins in the collections from the 1910s and 1920s that outlined who could swim at the community pool, and when.

Women, as nurses, were considered the equivalent of officers. They were accepted as a social part of the fort. At the end of WWI, with influenza ramping up, black women were allowed to enroll as nurses with the Army Nurse Corps through the Red Cross. They were assigned to certain posts in the Army, not necessarily at Fort Monroe.

Women enlist in Army medical unit

Women were open to enlist in 1943. Nurses’ quarters were constructed at Fort Monroe and nurses arrive in 1944. Women had their own barracks, mess hall, and were segregated from the male companies. They fall under the chief of staff for Army Field Forces.

At their time of enlistment, men and women received the same benefits and pay for the same rank. There were limitations placed on women for what rank they could reach until the 1970s. During WWII, their rank was usually captain or major.

The Army Corps of Nurses celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1951. The Fort Monroe collection includes medical unit lists of those women, souvenir menus and other items.

“(Women) become a very well-integrated part of the Army at that point, 1943 onward,” Ali said.

Ali shared an anecdote about Captain Elizabeth E. Steindel, who was chief nurse at Fort Monroe for about two years (1943-1945) during World War II. She was trained at Mercy Hospital in Altoona, Pennsylvania, and was commissioned as an Army nurse in 1942. She taught an accelerated course at the Fort Monroe station hospital to train nurse’s aides in 1945 – which sounds like a precursor to the CNA apprentice training currently offered by Virginia Health Services.

According to a newspaper article from the time, “the Monroe nurses get a certain amount of military drill and calisthenics.” The article also states there was “a staff of 12 handling a 139-bed hospital.”

Once Fort Eustis, Fort Story and Langley Air Force Base are established, the military dispersed medical stations around Hampton Roads.

The Fort Monroe hospital, which still stands on Ingalls Road, was converted to a clinic after the 1950s. Fort Monroe lost a lot of its operations, including maternity, which eventually was assigned to Langley AFB, Ali said.

The Women’s Army Corps (WAC) was inactive in 1974 and women were fully integrated into male units. By 1978, WAC dissolved into full integration in the Army.

Birth of occupational and physical therapy

Occupational and physical therapists also come out of WWI, then called reconstruction aides.

Near where the Hampton VA Hospital now stands was once the National Home for Disabled Volunteers, Ali said. It was a place for draftees to go to receive support for their “war neuroses.”

They were “asylum style hospitals; full-functioning communities for medical care,” though the underlying causes of mental health weren’t addressed at the time.

When the Army needed a demarcation hospital, it requisitioned the Hampton National Home and the veterans shifted to other hospitals in the U.S. Eventually it became General Hospital No. 43, which was geared toward mental health, shellshock and war neuroses, Ali said, to fulfill President Woodrow Wilson’s push to return soldiers to being “productive members of society.”

They added reconstruction aides, who were women trained privately through a hospital program and instituted programs to rehabilitate soldiers physically and mentally.

“It becomes the premiere neuro psychiatric facility of the Army” in Hampton, Ali said, and there were other locations.

One of the techniques the reconstruction aides used was weaving to help soldiers handle anxiety by occupying the mind. Programs were instituted and research was done that contributed to the occupational therapy program.

Occupational therapist Lois Clifford was assigned here in 1919 for the neuro-psychiatric hospital. She was trained occupational therapist and worked with soldiers with war neuroses. She was discharged from the Army with a “mental breakdown,” she calls it, and took time off for her recovery.

Clifford published a book on card weaving in 1947 and spent most of her life after her breakdown as occupational director at West PA School of the Blind.

The therapists fell under the Army medical department; no separate entity was created for reconstruction aides.

Virginia Health Services offers rehabilitation in its skilled nursing center units and outpatient physical, occupational and speech therapy. We recognize the important work women did as reconstruction aides to lay the groundwork for that field.